Capturing and analyzing the diversity of gender identities, disability, and geographic distribution among our panel of experts who help evaluate project proposals is quite straightforward. It’s less so for their race and ethnicity. Last year, Lever for Change started testing a demographic survey with closed-ended options for race and ethnicity that are granular enough to be globally relevant and allow us to spot patterns of inequality.

The goal of collecting demographic data from our panel of experts is to ensure that we have a diversity of perspectives and participation of individuals from groups who have historically been marginalized in the decision-making process.

While there is more agreement globally on suggested closed-ended categories to collect data on gender identity and disability, there is not yet global agreement for race and ethnicity. For our first few challenges, we surveyed expert reviewers using categories derived from U.S. forms such as the Census:

- African, African-American, or Black

- Asian or Asian-American

- Caucasian

- Hispanic or Latina/o/x

- Indigenous Person of the Americas

- Indigenous Person from a population category not provided: [open text box]

- Middle Eastern or North African

- Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander

- I prefer not to answer

The problem is that many of our challenges are global, and for many global respondents, these options may seem insufficient or arbitrary. Knowing the limitations of these categories, we included open space at the end of the survey to solicit feedback from respondents.

In one example, we received a response where the respondent selected the “Race/Ethnicity” option “Other” for its staff and explained why none of the categories we provided fit what the organization wants us (and potential funders) to know about them – in this case, that the organization specifically hires staff from Scheduled Tribes in India for its project to improve healthcare access to geographically isolated Scheduled Tribe communities.

I brought my own personal lens as I started thinking about a survey that might better capture nuances of inter-group relations around the world. Growing up in Southeast Asia, I was keenly aware of racial and interethnic tensions in countries such as Singapore between the ethnic Chinese, Malays, and Indians. Had a Singaporean organization advocating for building harmony among these three ethnic groups (with a board that had equal representation of individuals from all three) filled out our U.S.-centered survey, all that our data users would know is that that organization is led by “Asian/Asian-Americans.”

The goal of developing new categories for our survey was to move away from using U.S.-centric demographic categories that do not represent a global constituency and to move towards categories that ensured all respondents, regardless of location or cultural context, felt represented. In its first year, we have received positive feedback from respondents.

A new set of options with global inequality in mind

When I started my research, I wanted to understand how demographic surveys vary around the world. I came across the work of sociologist Ann Morning at New York University, who conducted a systematic review of official Censuses around the world. Her findings show that demographic surveys from around the world differ because they are all informed by locally specific contexts, such as history, migration patterns, geography, etc. Furthermore, there are a wide variety of definitions for the terms “race,” “ethnicity,” and “nationality.”

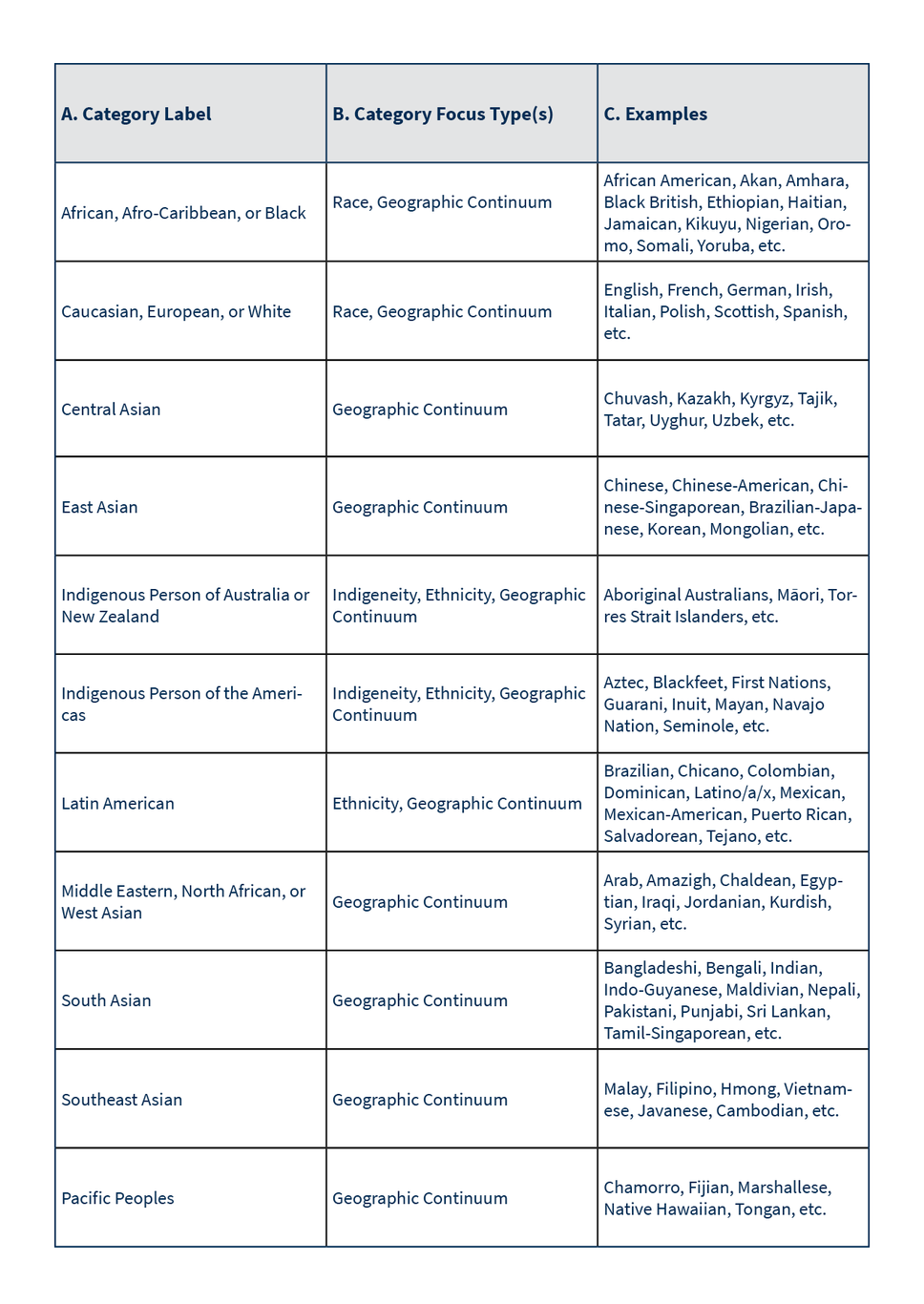

In that vein, the categories we now use for race/ethnicity data collection at Lever for Change (which you can find in the table below) were designed specifically for social impact projects in a global context, i.e., for the specific purpose of managing and tracking data related to funding for activities that improve the lives of individuals or communities.

While the categories were selected and defined to be as easily understood by as wide an audience as possible, and to capture inter-group dynamics in the context of globalization in a post-colonial world, we acknowledge that the classifications provided are not evergreen nor required to be universally applicable across non-social impact disciplines (e.g., linguistics, genealogy, anthropology, etc.). However, the categories should be applicable across the philanthropic sector, whether collecting data on funders, grantees, or beneficiaries in projects themed around education, environmental conservation, racial injustice, among others.

To date, we have used our new categories to survey more than 600 individuals from around the world who have contributed their expertise to evaluate applications proposing to solve the world’s most pressing issues. We have used the data to spot patterns, such as a lack of representation and inequality in our decision-making process (for example: are White, North American individuals overrepresented in our pool of experts?).

Global demographic categories as proxies for race and ethnicity

To accommodate for differing definitions, we offer respondents options that are categorical groups (Column A in the table below) of some widely understood races, ethnicities, and nationalities, as opposed to presenting categories framed as being a list of the races, ethnicities, and nationalities themselves. The inclusion of each option was motivated by one or more of four focus types (Column B).

The goal of developing new categories for our survey was to move away from using U.S.-centric demographic categories that do not represent a global constituency and to move towards categories that ensured all respondents, regardless of location or cultural context, felt represented.

Adi Menayang

Because of the social impact context of our data collection, these four focus types were developed based on global dynamics in a world still healing from Western colonialism. There is plenty of literature that catalogues which groups of people were legally and culturally disadvantaged during Western colonialism and imperialism, and which were privileged, due to criteria such as race or geographic location. The focus types are:

Race

Race has historically been used to classify people based on physical features. In Ann Morning’s systematic review of official censuses from around the world, the term ‘race’ was found almost entirely in the Censuses of former slaveholding societies of the Western Hemisphere and not found in European or Asian censuses. Although these are arbitrary classifications, race used in the manner above is widely understood and is also a proxy to the lived experiences of Black people around the world living under systemic racism and White supremacy. These two categories, Black and White, are kept as options for self-identification to allow our data to capture these collective experiences in analysis.

Geographic Continuum

Geographic continuum categories describe commonly accepted regions where there is a continuum of shared culture among countries within the region, such as Latin America or Southeast Asia. Numerous ethnicities and nationalities comprise each category that is focused on a geographic continuum, however the division of geographies we use in our data collection instruments correspond to historic patterns of migration, which in turn were shaped by colonial labor programs, treatises, spread of religion, military activity, and many other factors. The level of granularity for geographic continuums was designed to not overwhelm respondents but still allow data users to see more nuance regarding historic and persisting patterns of inequity, marginalization, and underrepresentation.

Ethnicity

Ethnicity is commonly understood as a group of people who share a language, tradition, customs, as well as shared memory of migration and/or colonization. Categories labeled as Ethnicity as one of its focus types indicate there is more emphasis on linguistic and cultural factors that may unite the people under this umbrella than in Race or Geographic Continuum categories. Latin America is a prime example—beyond a shared geography in the Americas, a distinct Latin American identity emerged due to language and immigration patterns.

Indigeneity

Based on Ann Morning’s 2015 analysis of world censuses, questions about indigenous status were used in censuses in the Americas and Oceania but absent in European and Asian censuses. “Indigeneity seems to serve as a marker largely in nations that experienced European colonialism, where it distinguishes populations that ostensibly do not have European ancestry or who inhabited the territory prior to European settlement.”

Because of the different indigenous experiences among populations around the world (e.g., an indigenous person of France in France versus an indigenous person of the Americas in the U.S.), the classification system that we use separates categories of indigeneity specifically for Indigenous People of the Americas and Indigenous People of Australia and New Zealand.

Each option is accompanied by a list of examples (Column C) to help respondents understand what we mean, not so that they “answer correctly” (as there are no correct or incorrect answers), but so that we can ensure data users and respondents use the same language when defining identities.

Respondents may select more than one category to indicate mixed identities or if they think their specific identity may straddle two or more categories we provide. Respondents are also given the option to answer: “I prefer not to provide this information” or “I don’t know.”

Four additional layers of questions

For better data capture of demographic representation in our programs, the question inviting respondents to select one or more of the race/ethnicity/nationality categories above is preceded by an open-ended question to let respondents self-describe their identity.

The question is followed by a closed-ended question to capture more nuance around indigeneity and historic, systemized marginalization that may not be captured by the question above:

Part 2: Are you part of a traditionally underrepresented or marginalized group in either your country of origin or country of current citizenship, whether officially recognized as such, partially recognized, or not recognized?

Examples of officially recognized minority groups include Scheduled Tribes in India; Irish Travelers, Roma, and Sami in Europe; Indigenous peoples in countries that have ratified the International Labour Organization (ILO) Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention No. 169; etc.

Examples of partially or not officially recognized minority groups include Native American tribes with only state-level recognition or no legal recognition at all; the Rohingya in South and Southeast Asia, etc.

- Yes

- No

- I don’t know

- I prefer not to answer

Finally, the respondents are invited to select as many options as they like from a list of 249 countries and territories with United Nations ISO codes to describe their country of citizenship and country of origin (which “may refer to your country of birth, parents’ country of birth, a country where you grew up, and more”).

What respondents are saying, and what comes next

The survey was developed with data collection from individuals in mind, which is why using the revised race and ethnicity categories in surveys of our global panel of expert reviewers was a natural start. Out of 663 respondents from 84 countries, 77 decided to fill in the optional feedback space. Here are some positive reactions, which comprise the majority of feedback:

- “I am glad you're even thinking about the subject! Current categories are (and always have been) inappropriate, and I consider this way of thinking to be progress.”

- “A very comprehensive approach with appropriate humility and willingness to learn and modify.”

- “I thought the survey was extremely thoughtful and well-done.”

- “Thank you for asking these questions and hope you can always prioritize your commitment to diversity! This is great.”

- “I have no recommendation, rather I want to congratulate you for the inclusiveness in this form.”

We also heard back from individuals who were not so keen on the survey:

- “Way too many questions about identities that may or may not tell you very much about a person.”

- “You could inquire about the Ancestry or 23andDNA results.”

We continue to collect feedback from respondents and our stakeholders to ensure we can analyze and report on the diversity and inclusivity of our decision-making process.

The next step was to modify this form to collect data on the diversity of organizations (and their leadership) among our pool of applicants, finalists, and awardees. Our data policy at Lever for Change places a high importance on self-identification, hence, the form discussed in this piece, with its strong focus on individuals, is inadequate. This led to our team developing an entirely different form, which we piloted this year for capturing data on organizations.

We plan to continue updating our surveys and categories to reflect our changing world and to remain intentionally inclusive by design. In the meantime, we’re always open to feedback on our demographic survey for individuals and would love to hear your thoughts. Also, we encourage you to sign up for our news updates. Stay tuned for more on this topic soon!